Everybody Loves Jarren Duran — The Mental Health Conversation

Jarren Duran (Maddie Malhotra/Boston Red Sox/Getty Images)

It’s 2022, and another warm, mid-summer twilight in Boston. Raimel Tapia steps to the plate with 2 outs in the third, bases loaded, and the Blue Jays are already crushing the Red Sox 6-0. Tapia hits a deep fly to dead-center, and Jarren Duran, the young Sox prospect, can’t find the ball in the lights. He looks lost and dumbfounded, innocently holding his palms up in a pleading shrug to show he is doing his best but has no idea what to do. It’s a universal signal of helplessness, but it’s interesting, and provides the beginning to our story.

Raimel Tapia hits an inside-the-park Grand Slam against the Boston Red Sox, July 22, 2022. https://www.bleachernation.com/cubs/2022/07/22/yes-this-is-the-most-ridiculous-inside-the-park-grand-slam-you-will-ever-see/

The 2022 Doldrums

The Red Sox called up one of their most elite prospects in 2021 – Jarren Duran – who had seen startling, base-stealing success despite being a 7th round no-name from Long Beach State. With elite, 80-grade speed and an .869 OPS in Triple-A Worcester, it was time for Jarren Duran to get a crack. He laced a single in his debut at-bat against Cy Young Award-winner Gerrit Cole, and a couple days later, hit his first home run. But the season turned grim as his aggressive approach got exposed under the bright lights of the Show. Duran wrapped the 2021 season with a meager .215 batting average and an OPS+ of 53 (contrast this to his .439 wOBA since the 2025 All Star break, as of this writing). The Red Sox made the playoffs in a Cinderella way, edging out the first-place New York Yankees in the new Wild Card format, storming all the way to the ALCS against Houston. However, as the page turned to 2022, the team looked lost and searching for its identity.

Between the 2004-2018 glory years of Manny and Big Papi to Mookie Betts, Chris Sale and Bogaerts, it felt like the 2022 team was an afterthought of the franchise – the scraps of an indecisive rebuild. To some, it felt like the ownership was looking to cash in on a dedicated, Fenway faithful who were still buzzing from Dave Roberts’ stolen base, and that was enough to be grateful for, no matter if their stars landed in the west. The 2022 Red Sox finished in last place with a 78-84 record. Boston sports radio producer Jimmy Stewart shared his thoughts: “Epic fail by this team … This is one of the worst Red Sox seasons of the last twenty years.” Incidentally, Hall of Famer and NESN color commentator Dennis Eckersley retired from broadcasting at the end of the season. This is the depressive, low-energy context of the 2022 season for the Red Sox.

Duran Under the Glare

Tapia’s big hit went viral as Duran’s folly – he was spit-roasted on social media for not even running after the ball he’d lost in the lights. We’ll go through some notable quotes from that night that showcase where we are going in this story.

“I just lost it in the twilight … It’s the most helpless feeling you could ever feel.”

As for why he didn’t hustle, Duran had this to say:

”Dugie was right there already … Obviously I should have taken a step or two. But he was already going to beat me to the ball so I just didn’t want to get in his way. What if I sprinted and collided with him or something like that? But next time I know to take one or two steps.”

I don’t think Duran didn’t hustle. Notice that his words aren’t the usual, PR-proof screen-saver of the modern athlete, some unobjectionable filler along the lines of “my bad, I will work to be better next time”. His words show this real sincerity – this pleading fear for others to understand his innocence: it’s the most helpless feeling you could ever feel. He didn’t say “that I’ve ever felt”. This speaks of shame – a primary concern with how others see him. Moreover, when he says, “But next time, I know to take one or two steps”, it feels partly tongue-and-cheek but also like a servile bow to the critics – I will obey if you just accept me. Please, look elsewhere. This idea of optics – the all-seeing wrath of sports fans with smartphones, is a theme that stalks Duran on and off the field.

“I feel like people see us as zoo animals sometimes [be]cause we’re in this big old cage. People are trying to throw popcorn at you, get a picture with you, get your attention, scream your name.”

Later that season, tormented by failure and the loneliest despair, Duran tried to take his own life. In the fourth episode of the Netflix series, The Clubhouse, entitled "Still Alive”, Duran shares:

“I got to a point where I was sitting in my room, I had my rifle and I had a bullet and I pulled the trigger and the gun clicked, but nothing happened. So, to this day, I think God just didn't let me take my own life because I seriously don't know why it didn't go off.”

No Separation

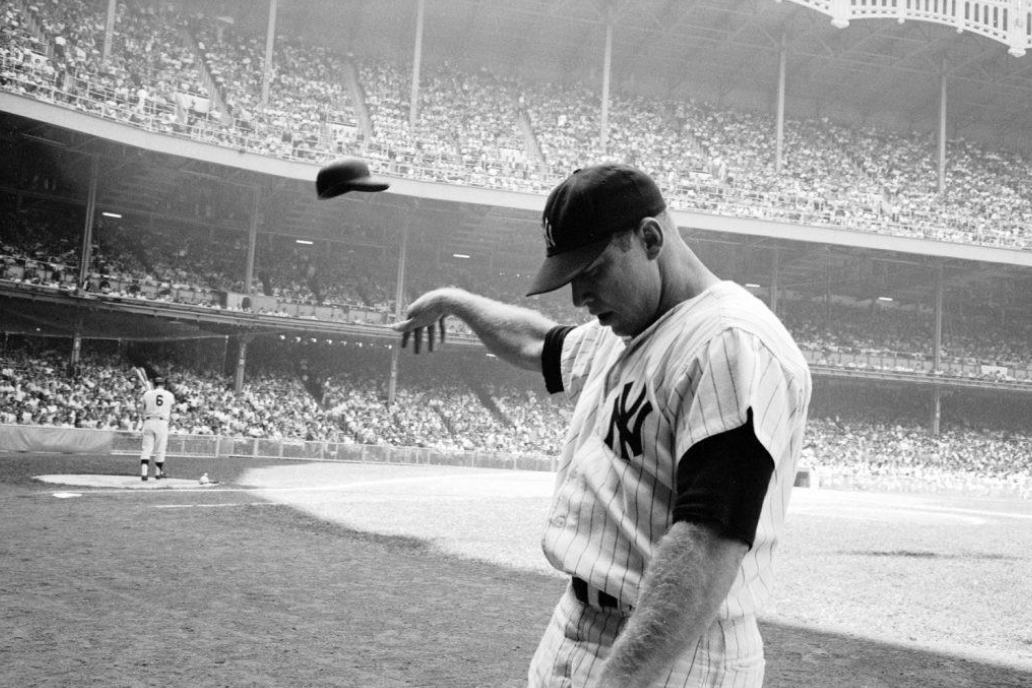

Modern mental health talk in the sports arena has made big strides. Looking back, you have guys like Mickey Mantle dying of alcoholism, suffering the pressure of being everyone’s childhood idol, chasing Babe Ruth, while playing the most public game of failure. Giving players the room to grow and be human is wonderful.

Mickey Mantle tosses away his helmet in disgust, Yankee Stadium, June 1965 - https://www.reddit.com/r/baseball/comments/1gtj568/33yearold_mickey_mantlehis_electrifying_talents/

Yet, I think we can do better. I worry that the phrase “mental health”, in the sports context, as showcased with Duran, can take this off-ramp that elevates a few struggling spokesmen, and encourages some to seek help. That sounds great on the surface. However, I think this forsakes the bigger picture for a sound byte. The kind of struggles Duran has shouldn’t be some pathologized, discrete thing we just fence off and feel bad for. It seems to me that the mental health conversation in baseball becomes almost a trademark, like a fad that stops at pity and doesn’t enter the cave of self-examination. It congratulates itself on tweeting about the struggling heroes, puts them on a pedestal, and moves on. But life moves on with it. In a way, rather than these players becoming mirrors for us, they become sacrificial offerings we give a label to, ostensibly elevating them with words like “brave”, but we’re really washing our hands of our own introspection. Society has done its duty of compassion INC – no more to see here.

The Bigger Picture

But compassion’s real etymology is to suffer with. I think life, in a spiritual sense, is a struggle with emptiness and good things ending, and our utter powerlessness to ignore it. This doesn’t make for very good MLB advertisements, nor clickbait for that matter. Maybe for some, they try to drown this emptiness out with addiction, and others turn inward, buying into the head gremlins that say you’re not enough.

With Duran, some may say he’s a strong hero, simply for opening up about his struggles. I think he’s both more and less than that. I think he is just a human being, not a poor brain that’s having a uniquely hard time – and not to his discredit. In his own words, Duran notes that he doesn’t want to be on some mental health pedestal, “it just triggered me when you start talking about mental health … I feel like that’s just part of it … is that loneliness. Some people deal with it better than others”. Indeed, I think we all have an allergy to life, taking the form of a loneliness that feels like it’s waiting for us, gnawing at the shadows just outside the ring of the campfire’s glow. We all strike out. We’re all powerless; we’re all impermanent. If you don’t buy that, here’s a simple one: let your eyes go out of focus, and wait for a “floater” to appear in your ambient vision. Try to stare at it, and hold it there from running out of view. Try to yell at the ocean waves to stop, and try to not worry about Monday.

Powerlessness doesn’t mean helplessness, however. I think the mental health discussion in sports needs to widen its scope from being so focused on “affected” players, as if they’ve caught some cold amidst their synapses, and shift to the fact that this is just the human condition. Instead, to me at least, it seems the media stops at this point of the conversation just to note how great it is we’re talking about it. It feels self-congratulatory and incomplete, like Duran has re-become the zoo animal in the cage he fears he is. Cubbied away as a guy that struggles, the warm acceptance of de-stigmitization of mental health only lasts so long, like a morphine drip to brutal pain. Again, life goes on, and the pain comes back around. What once was a pedestal of being the mental health hero has shifted to the pathologized museum oddity (insert cloying, gameshow host voice here) we’re just so proud of as a society.

It would be one thing to write a piece that condemns the Cleveland fan that heckled him this year in April, who said he should have killed himself when he had the chance. Screw that guy. But here’s some brutal honesty: I myself have said terrible things in private when watching men fail in sports. If a guy does poorly or gives up a home run with 2 outs and 2 strikes and my team loses, I’ll let off some invective venom that, if it were played back in a courtroom, I’d wither with remorse. I have to own that and keep it real, just like Duran does. One day at a time.

Jarren Duran poses with youth baseball in Mexico during a preseason game in Mexico City - Jarren Duran’s Instagram @duranjarren

Similarly, imagine how Duran felt when he shouted the homophobic slur at a heckling fan while batting during an August, 2024 game against the Astros. He went through the regular proceedings of a public apology, a penalty, a donation, and a promise to seek sensitivity training. Nominally, he made amends. But I think we can do better than trying to shoe-horn a slur into a scale of good versus bad. I think this instance humanizes Duran and showcases the larger story. Mental health isn’t this drive-through window of “wow how brave” – it’s a breathing, infinite human mind harshly grating against a finite and more powerful reality than us – what we all endure moment to moment. Maybe that fan deserved to be yelled at. Maybe Duran exploded from excruciating internal pain and didn’t wake up that day premeditating a way to marginalize people. I believe that’s the case. Yes, people in the spotlight bear a responsibility to operate at a higher standard, but contrary to the same media that vaguely praises him for sharing his struggles then condemns him as a bigot, we need something closer to the mark.

Everybody Loves Jarren Duran

Duran’s story shows that baseball is the athlete’s perfect microcosm of intense public failure. Bill Buckner’s missed ground ball, Duran’s lost pop fly, his homophobic slur, a player striking out in a critical moment – these failures happen under a literal spotlight: televised, recorded, retweeted and replayed. It’s like you are at your job, missed an email about an important meeting, and everyone at the company puts you in a glass box to laugh at you for a few weeks. If you slip up and yell back some expletive or something more regrettable, you lose your pay and are dragged back into the glass box with nowhere to hide. The nightmare never ends, leaving you at the jumping off place: get a mask, a substance, or so much success you’re free from the prying eyes of the camera – until the next mistake.

I would argue that Duran is neither weak, nor exceedingly strong, nor perfect or immune to criticism. I think he is an incredibly-attuned individual, an instrument that feels and experiences deeply. I’m reminded of that line of Hafiz, “I am the hole in the flute that the Christ’s breath moves through”. The emptiness of let down and the despair of public failure, plus hiding it poorly in raw ways bears witness to the suffering of life, and gives us fans a new way to spectate what’s really going on with ourselves. The player becomes the hole in the flute – an emptiness catching the winds of success and failure. What music may come. This is his superpower and his gift to us. This is why he inspires me. His strength lies in the humility of just being human – he comes as he is. As covered in prior pieces here at Painting Corners, this is the refreshing stuff that makes you fall in love with baseball.

Jarren Duran is congratulated in the dugout after scoring against the Dodgers at Fenway Park, July 25 - https://www.newsweek.com/sports/mlb/red-sox-facing-tricky-jarren-duran-decision-following-roman-anthony-news-2110361

When I read his quote about the missed pop fly in Fenway, I felt, as William James has said, “....a native hardness begin to liquefy.” I was reminded of something in his words that desperately sought forgiveness. To be clear, he doesn’t need forgiveness for losing a ball in the July twilight – or at least, I don’t think so, but I think in his quote we get a glimpse at the heart of the matter. Duran was dying to be understood, in a posture that can’t hide behind the blades of the centerfield grass. He didn’t turn around and run to the ball – not because of indifference, but because of shame. At that moment, I bet his whole body was frozen, and his legs felt like sand. This reminds me of what it feels like to make a mistake at work. Moreover, the shame is really just pride in reverse. When I feel shame, I’m communicating to the universe that I’m too good to make a mistake – there’s no humility in that. Contrast this, however, to sloganeering that it’s okay to mess up all the time because that’s just what you do. On one hand, there is a prideful fear of being rejected, and on the other, a vague tautology that doesn’t strive to improve. Duran’s own handwriting on his gameday wrist tape provides the clue through these extremes: Fuck ‘Em, and Still Alive. That’s not just to haters and hecklers, but to the gremlins of doubt as well as pride, lurking within our very minds.

I don’t think Jarren Duran is a victim or a specimen, and I don’t know if he is a hero because of mental health. I think he is a human being that bears witness to the drama of life on the brightest stage. To continue doing so without killing yourself under intense pressure is heroic. I hope the conversation on mental health enters its new evolutionary phase. In the Mantle era, the only option was to try to appear stoic, keeping whatever crutches you needed to seem even-keel, off stage – stowing the bottles under the bed and wearing strained smiles in photo ops. Now, we’re at a place where there’s a capital-C Conversation around mental health, and my concern is that we stop there, self-satisfied with a slogan and a new social media campaign. I think it’s time to be honest and admit that life is very painful. We have a hard time in quiet moments because they remind us of death – all the better reason to fill it with chatter and gossip. Jarren Duran’s highs and lows provide a humbling story that’s a lot closer to the reality we should strive for. In public, he is how we are in private. It’s not courageous to just be an asshole or to whimper in complaint. But it is damn cool to watch a man grow in real time, and not hide from the game we all suit up for everyday.